This job is about creativity, entertainment, passing along knowledge, and being a good listener. We get to hear some of our visitors’ histories. Their history is always interesting too!

1. What led you to the mission of being a curator of education?

I was interning and attending school. I had previously been an elementary school teacher and had gone back to school to pursue a second degree in art. During that process the Curator of Education left that position. I asked, “What does it take to  earn that job?” I was told, “You have to have a teacher’s degree.” There were also other requirements. I met all the requirements, so I applied for the job. The outcome was that I was hired. However, I had to stop taking the classes I was in and not continue the second degree I was after.

earn that job?” I was told, “You have to have a teacher’s degree.” There were also other requirements. I met all the requirements, so I applied for the job. The outcome was that I was hired. However, I had to stop taking the classes I was in and not continue the second degree I was after.

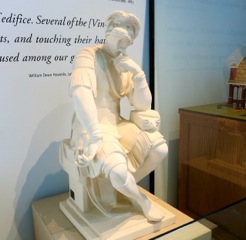

As the Curator of Education at the Crisp Museum in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, I get to teach art, regional history, interact with the public, and provide a weekly family day at the museum. We also have tour groups and student classes that come through — such as college classes that are learning about things we have on display at the museum.

We have an outreach program for the community and provide a museum summer academy, gallery talks and lectures, and opportunities for people to be docents and volunteers. Also, people come in to the Crisp Museum to study and display art.

2. What does this mission mean to you?

I get to make this job anything that I want to make out of it – anything that is educational, interesting to the teachers, along curriculum lines, or interactive with the educational classroom. I can also bring something to light that might be new and very, very creative.

There are conferences for museums. I am able to go and meet other curators. We get ideas from each other. An example of something new and creative might be to invite someone special to talk and explain the exhibits. Instead of going to the museum and just looking at objects, looking at labels, and going from one display to the next, we might have someone there that you can talk to – someone who can introduce the object, and explain who created this object, what this object was made for, and how it was used. This person might ask questions that help the student think deeply, “Do you see the wear and tear? How do you think this wear and tear got there?”

and meet other curators. We get ideas from each other. An example of something new and creative might be to invite someone special to talk and explain the exhibits. Instead of going to the museum and just looking at objects, looking at labels, and going from one display to the next, we might have someone there that you can talk to – someone who can introduce the object, and explain who created this object, what this object was made for, and how it was used. This person might ask questions that help the student think deeply, “Do you see the wear and tear? How do you think this wear and tear got there?”

If you have prehistoric stone lithic such as spades, parts of those will get glossy because they were used over and over again as tools. All the time this tool went down into the soil, it became glossier on the end.

There may be stories behind the ceramics in the  collection. The docent or curator can tell stories about the patterning that was used, if the ceramic has a glaze, and what natural materials or resources were used to make the piece. Afterwards, children and adults can actually do some activities related to the displays. One family day, we studied some things in the museum and then the family members actually did a related project by getting to dye something.

collection. The docent or curator can tell stories about the patterning that was used, if the ceramic has a glaze, and what natural materials or resources were used to make the piece. Afterwards, children and adults can actually do some activities related to the displays. One family day, we studied some things in the museum and then the family members actually did a related project by getting to dye something.

We have files and notes on most of the pieces. Even if the piece doesn’t have handles, it might have had them at some point in history. This would be documented in these files. The notes also tell if there are such things as a pressed fingerprint on the artifact. Perhaps the print is so small that the observer will note that the print was probably that of a child who created this piece. Those are of the kind of things that the curator gets to tell people who would not naturally know these facts just by seeing the piece on display.

3. What was your best day as a curator of education?

Tuesdays! Every Tuesday! We do a program called Tuesday At The Museum. They are free programs offered to adults and children. The children can be aged three to fifteen. It is always fun! I think we  have only missed one or two Tuesdays for the last six or seven years!

have only missed one or two Tuesdays for the last six or seven years!

We focus on art, art history, talking about masters of art, or something going on the gallery. We might tour the gallery, look at the pieces, and then go into the classroom and try to recreate some part of them. This doesn’t mean the project is going to be tedious and hard. Children might be shown a certain type of material that was used in the past and the teacher will ask, “If I give you these same supplies, what can you do with them?”

4. What was your worst day as a curator of education?

There really isn’t a worst day; there are just difficult instances in a day. As a curator, you become very protective of your objects and you don’t want  anything to happen to them. You stick to your rules – certain things you can touch and some you cannot touch. You have to tell the rules before you go on the tour. I may sound a little strict, but for the long haul, the rules are going to make sense. I want the objects to remain just as they are and not to deteriorate!

anything to happen to them. You stick to your rules – certain things you can touch and some you cannot touch. You have to tell the rules before you go on the tour. I may sound a little strict, but for the long haul, the rules are going to make sense. I want the objects to remain just as they are and not to deteriorate!

We had an accident one day. It was just from a little bit of rowdiness. A moveable wall fell in the art gallery. A couple of kids decided to play tag around it. The wall fell and we were very concerned because there was a high dollar piece of art hanging on that wall. Nothing was damaged. But, in those instances you can say, “From now on do this…and this is why…. and this is why we are so protective: We don’t want anything damaged.”

5. How did you survive your worst day?

The worst-case moments are just short happenings. There is an instant, it happens, and we go on. It is not something that is continual.

This type of job is about creativity, entertainment, passing along knowledge, and being a good listener. An object can spark a memory and a person will start telling you stories. We get to hear some of our visitors’ histories. Their history is always interesting too!

If you are at all interested in educating, being a curator of education is fantastic because you can impart all this knowledge and you don’t have to spend time grading papers. You are here for interest, and exploration, and for people to see all the things that are waiting for them inside the museum.

- « Previous person: Miriam Ahmad

- » Next person: Faith Barnes