If someone has a calling… Give the time to it. Once you open yourself to that calling, things take their own dynamic. I remember the first day that I did a leaf cube. It was there and I said to the cube, “You’re interesting. Let’s see where we can go.”

1. What led you to the mission of being a sculptural artist?

It has been a long path and long way to becoming a sculptural artist. I don’t think that that way is finished yet. It is still developing. Bringing my different strengths together has made me an artist. One of them is that I love working with my hands.

Being a sculptural artist started in my childhood. I’ve always loved any kind of craft. My grandmother and mother were keen knitters. My grandmother was also a seamstress. I remember my grandmother having a big sewing machine. I’d be sitting underneath there making things with scraps of fabric. I just loved constructing things. I made little landscapes out of paper and matchboxes. I learned how to crochet. That craft side of me was always there.

Being a sculptural artist started in my childhood. I’ve always loved any kind of craft. My grandmother and mother were keen knitters. My grandmother was also a seamstress. I remember my grandmother having a big sewing machine. I’d be sitting underneath there making things with scraps of fabric. I just loved constructing things. I made little landscapes out of paper and matchboxes. I learned how to crochet. That craft side of me was always there.

I’ve always also had a love for nature. I loved gardening. My grandmother and my mom implanted that love of nature within me. I remember growing a carrot, going for a walk, seeing the beach. Anything like this was really strong to me.

After school, my first thought was to study landscape architecture. That didn’t feel completely quite right and I discovered something else — model making.  Model making was to learn to make anything you can with your hands. I dropped the studies in landscaping, dropped the degree and did an apprenticeship with a company with product models. The models were very, very crisp, very precise, and this met my love for precision. In those three years of apprenticeship, I learned so much in terms of making and training my hands. I learned so many more skills and how to use many different materials. I loved it. I was really happy in that time.

Model making was to learn to make anything you can with your hands. I dropped the studies in landscaping, dropped the degree and did an apprenticeship with a company with product models. The models were very, very crisp, very precise, and this met my love for precision. In those three years of apprenticeship, I learned so much in terms of making and training my hands. I learned so many more skills and how to use many different materials. I loved it. I was really happy in that time.

In my apprenticeship I made models for products like coffee machines and telephones and computers before they went into production. A designer would design a new model for a telephone. There might be three different versions of that telephone. Then he would come to the model makers and ask, “Can you make this?” So I would take a material like plastic and make a model that would look like the new mobile telephone. It was a complete make-believe world to make replicas of things like mobile phones and coffee makers.

In the special effects world I might make a giant chocolate bar to be used in a commercial or a spaceship or a creature or a robot or something like that.  If you see a strawberry in a yogurt ad, that is very rarely a real strawberry. It is probably a model that is made to look like the perfect strawberry. They do this for other things like cat food in commercials. I made biscuits out of wax for a book cover picture. It was a funny career.

If you see a strawberry in a yogurt ad, that is very rarely a real strawberry. It is probably a model that is made to look like the perfect strawberry. They do this for other things like cat food in commercials. I made biscuits out of wax for a book cover picture. It was a funny career.

You’ve got all these films like Harry Potter and Star Wars. A lot of modern special effects are done on the computer, but most still have their origins on a model maker’s bench or even before that from a graphic designer or animator’s drawing. Then the drawing comes to the workshop and the item gets made.

I think that is what always fascinated me about this job. It was never the same. I had a basic knowledge of many things – a Jack-of-all-trades. That’s who I am. I could do a little bit of everything… but not everything.

I wanted to work in special effects. I wanted to incorporate my love of art. My creative spirit wasn’t quite met in the constraints of model making for the designers. I packed my bags and went to London. I went with only photos of my work and a very basic knowledge of English.

I went and knocked on some doors. I think that is what I have always had in my life – a little inner feeling, “Oh this might be interesting.” Then I would go and have a look.  I didn’t really have a plan of where I was supposed to go. I didn’t think, “I’m going to do this. I’m going to live in London. I’m going to become a model maker.” It wasn’t like that. Before this time, there was a list of model makers and special effects in London and it sat on my desk for about a half of a year. It was just sitting there as if it was a little calling. I listened as I have so often in my life and said, “Oh this could be interesting. I’ll go and have a look.”

I didn’t really have a plan of where I was supposed to go. I didn’t think, “I’m going to do this. I’m going to live in London. I’m going to become a model maker.” It wasn’t like that. Before this time, there was a list of model makers and special effects in London and it sat on my desk for about a half of a year. It was just sitting there as if it was a little calling. I listened as I have so often in my life and said, “Oh this could be interesting. I’ll go and have a look.”

Once you open yourself to that calling, things take on their own dynamic. Within a week after moving to London, I had met a whole lot of companies and people who said, “Yep, right. Come work with us.” I went back home and handed in my notice to the work where I was employed. I said, “Right, I’m going to go and do this.”

I worked in the model making business – a difficult one. It is a very harsh industry. I went quite high up in that world. I worked a lot of hours. It was very, very stressful. I still loved the work. But it reached a point where it just wasn’t right any more. Something else needed to come in.

Typically people study art after they finish their schooling.  They find out what they want to do at school. I went backwards. I was putting a lot of hours in for my day job, my model making work. I always loved making things, having a craft, and doing things along side my work. But then I had a period of unrest. It came to me, “I’m going to art school.”

They find out what they want to do at school. I went backwards. I was putting a lot of hours in for my day job, my model making work. I always loved making things, having a craft, and doing things along side my work. But then I had a period of unrest. It came to me, “I’m going to art school.”

I went on Fridays, my college day to school. I was so scared and thought, “I can’t do this. No one is going to accept this. I can’t work and go to school on Fridays.” But I was able to find this course and went to the introductory day. I just thought, “This is what I’ve got to do. I’ve got to go there. There is no way around it.”

I did this for two years. I worked and shifted my schooling around it. It just worked. It was at that time that things came together. I was able to bring in the natural world. I was able to go to Cornwell and be in a place that was the opposite of London. I was able to spend all my free time coming to the very southwest tip of England. The nature came back in and I had projects at the college course that really challenged my thinking and my making. It was then that the first seeds of the work that I do now got planted.

2. What does this mission mean to you?

This was a fusion — a lot of things that I liked really came together. I’ve had a lot of doubts always going on, but this feels right. I get these confirmations every so often when I make a new piece of work. Some good opportunity comes about and I say, “Yeah. This is right.” It’s taken on this dynamic from making the first pieces – the seeds of ideas I planted in college to the seeds that have grown from there to now. That for me is the proof that I am on the right pathway.

3. What was your best day being a sculptural artist?

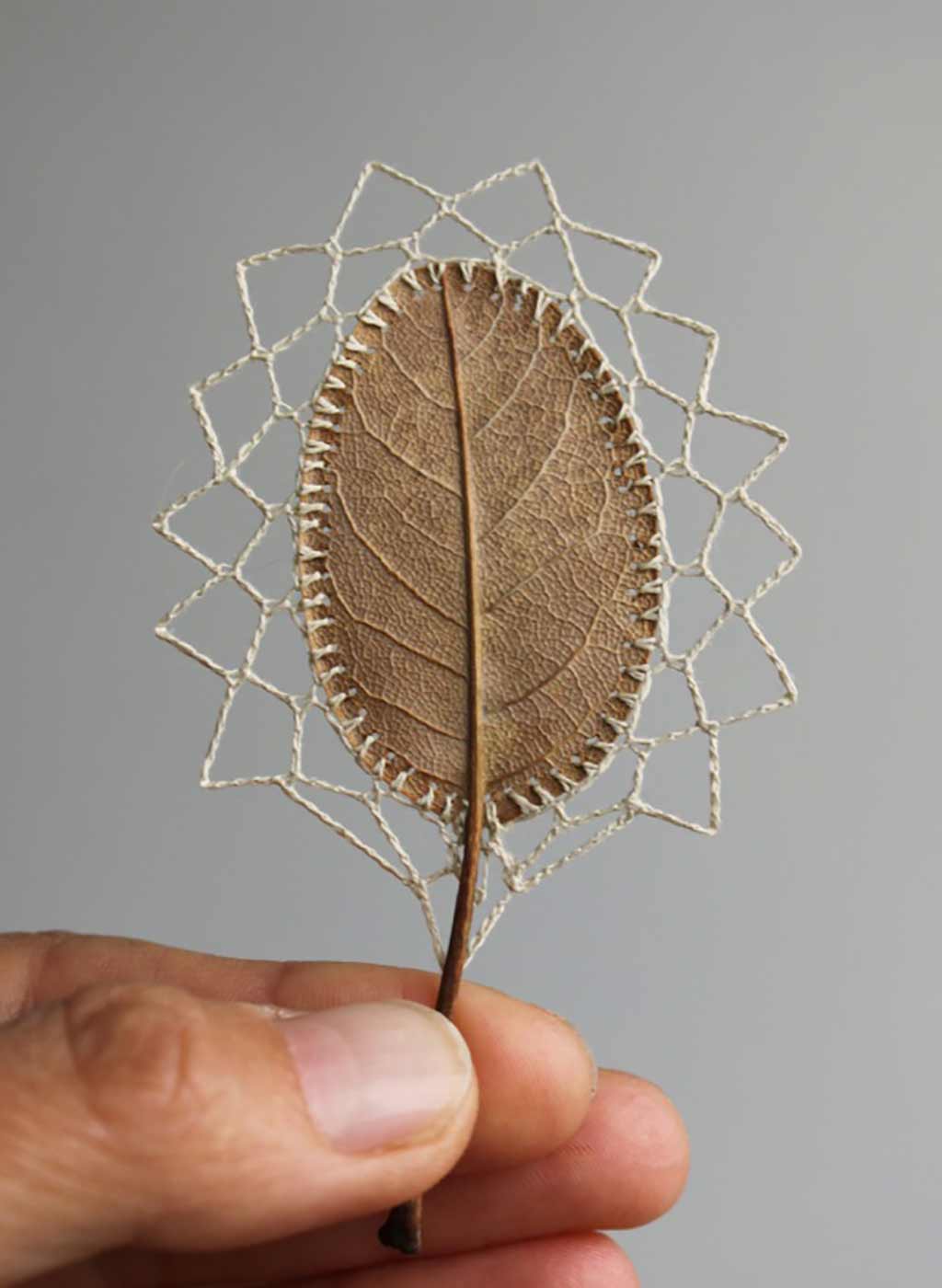

I remember the first day that I did a leaf cube. I was in Cornwall and had an idea. I don’t know where this idea came from exactly.  I had done some work with things and crocheting before. But it was this fusion of thinking, “Right… 3-D works of art. I’m going to try to see if I can make a cube out of a leaf.” It was just a little flash and I made this very rough looking leaf cube in an evening.

I had done some work with things and crocheting before. But it was this fusion of thinking, “Right… 3-D works of art. I’m going to try to see if I can make a cube out of a leaf.” It was just a little flash and I made this very rough looking leaf cube in an evening.

I was in the room on my own getting this thing together and thought, “What is happening here? This looks really strange.” I put it on the table and looked at it and said, “Oh. This could really go somewhere.” I went to bed and fell asleep with a very peculiar feeling of happiness, of surprise. It was just very strange. I woke up and this thing was still sitting on the table. It wasn’t a dream. It was there and I said to the cube, “You’re interesting. Let’s see where we can go.”

4. What was your worst day being a sculptural artist?

I don’t think I can pick out a particular worst day.  The worst days are the days of doubt — days when the questions come in. It is almost like when that little negative gremlin on my shoulder starts shouting in my ear too much – when the question comes in, “What am I doing stitching leaves together? What? That doesn’t make sense.” Or it is when I think, “Oh my God. What about money? Time? Commitment? How can I fit it all in? Where’s the next show coming from? What am I going to do with all this stuff? Can I take on another studio? I’ve got no more ideas.” All these things make it a bad moment.

The worst days are the days of doubt — days when the questions come in. It is almost like when that little negative gremlin on my shoulder starts shouting in my ear too much – when the question comes in, “What am I doing stitching leaves together? What? That doesn’t make sense.” Or it is when I think, “Oh my God. What about money? Time? Commitment? How can I fit it all in? Where’s the next show coming from? What am I going to do with all this stuff? Can I take on another studio? I’ve got no more ideas.” All these things make it a bad moment.

Or it is when I start to project too far in the future. “What am I going to do next year? What’s going to happen next summer?” It’s when the future questions get too loud.

5. How do you survive your worst days?

The one thing that throws up all these questions is the same thing that makes them all go away.  This is work. I just keep turning up. I just keep turning up and if I haven’t got a new thing to work on then I might just tidy up the studio or look at all the leaves that I’ve got in my little press wallets and ask, “What can I do with them?” I just turn up. I just try to keep going.

This is work. I just keep turning up. I just keep turning up and if I haven’t got a new thing to work on then I might just tidy up the studio or look at all the leaves that I’ve got in my little press wallets and ask, “What can I do with them?” I just turn up. I just try to keep going.

A hard day is when I am at the studio and I’m having a hard day and things just aren’t right. I think, “I’m not quitting. I’m just going for a walk. I’m just going out.” This is very helpful to bringing me back to the present moment. I’m very lucky that I’ve got a five-year-old boy. He is the best thing to bring me back to the right here and right now. Playing with him is the best cure. It instantly stops any of the worries. They just get shoved away and don’t get attention any more. When the times come around again to go to the workshop, then I am already in a different state. The work flows again.

The other thing is to believe. Rather than projecting and looking at what could have been or what I should have done or what I should do, I look at what is there. What is there? What have I got? It might be looking at the pieces of work I have at the studio and comparing them to where I was five years back and seeing what actually happened in the time between. I look at what universal conspiring fell into place to bring me further. I’ve learned to trust the idea that something will happen and something will help.

The other thing is to believe. Rather than projecting and looking at what could have been or what I should have done or what I should do, I look at what is there. What is there? What have I got? It might be looking at the pieces of work I have at the studio and comparing them to where I was five years back and seeing what actually happened in the time between. I look at what universal conspiring fell into place to bring me further. I’ve learned to trust the idea that something will happen and something will help.

Sometimes it is an action some people call God or some people call the universe or the creative genius or an angel or something else, and I say, “I talked to that something and asked, ‘Hey. Hey. I need a little bit of help. Can you get me through this?’”

I’ve experienced this universal conspiring so many times. If something feels right and I feel it from the bottom of my heart, or I have a real feeling that, “I’d like to do this now”, then something falls into place. Either I meet the right person or the right college course comes up or I make my step to England and meet the right combination of people to get me exactly to that next step that I need to take.

I’ve experienced this universal conspiring so many times. If something feels right and I feel it from the bottom of my heart, or I have a real feeling that, “I’d like to do this now”, then something falls into place. Either I meet the right person or the right college course comes up or I make my step to England and meet the right combination of people to get me exactly to that next step that I need to take.

I can’t really say, “I want that or I want this.” It is more like I’m following an instinct. I think that has always been the case. When I’m having my moments of doubt, or my wobbly days, then I just need to remember that this universal conspiring is still there.

6. What advice do you have for someone who would like to pursue a mission?

My biggest advice is to put the time in. Dedicate the time to it. I think the difficulty is that if you wanted to be a sculptural artist, you might start looking at the other artists to see pictures on the Internet.  You might say, “Yeah. That is what I want to be doing.” But you are looking at some work that people might have spent their whole lives not necessarily making but preparing for. That often gets forgotten.

You might say, “Yeah. That is what I want to be doing.” But you are looking at some work that people might have spent their whole lives not necessarily making but preparing for. That often gets forgotten.

I think a big hindrance is when you put something out front that you want to achieve but you don’t realize that you have to put the time in the find out what it is that makes your heart sing. If you like velvet, go and get some velvet and rub it for a week. It doesn’t have to come out to be a big fabric sculpture. It might just turn out to be something completely different. Put the time in to think about what really interests you. Then once you have found something then do that something. I’ve spent many hours crocheting and then adding leaves.

If you like painting, don’t paint with the masterpiece in mind. Just enjoy and feel how the brush and the paper feel for you. Do you like that red or is that other red better? It’s just about you and not the world outside. Just keep turning up. Put the time in and just keep turning up even if you don’t feel like it. Sometimes it is so very difficult to turn up to work or to spend time you have dedicated to that inner calling when you don’t know exactly what to do. But sometimes turning up at your designated corner of the table to shuffle a bit of paper around, will trigger something, rather than sitting on the sofa and watching TV without a bit of inspiration. Go. Turn up. Do it.

If you like painting, don’t paint with the masterpiece in mind. Just enjoy and feel how the brush and the paper feel for you. Do you like that red or is that other red better? It’s just about you and not the world outside. Just keep turning up. Put the time in and just keep turning up even if you don’t feel like it. Sometimes it is so very difficult to turn up to work or to spend time you have dedicated to that inner calling when you don’t know exactly what to do. But sometimes turning up at your designated corner of the table to shuffle a bit of paper around, will trigger something, rather than sitting on the sofa and watching TV without a bit of inspiration. Go. Turn up. Do it.

I just recently read again about the famous dancer called Martha Graham. She has some wonderful quotes. One of them was in answer to the question she was asked, “What can someone do to become a dancer?” She just said to just do it, just do it. (Note: One iteration of Martha Graham’s quote is: “Nobody cares if you can’t dance well. Just get up and dance. Great dancers are not great because of their technique, they are great because of their passion.”)

I had a calling for doing a pottery course in the middle of my artist’s way. I loved throwing pots and it was really a meditation to do so. The very person running that course told his gallery about my work and that is the place where I am now going to have a solo show in the summer of 2015. So in fact the reason why I am having a solo show this summer is because I thought I needed to have some down time and I needed to do some pottery. I made get some good bowls to eat my cereal out of, but it wasn’t that the universe needed me to become a potter; it just needed for me to make a connection between my pottery teacher and the gallery.

I had a calling for doing a pottery course in the middle of my artist’s way. I loved throwing pots and it was really a meditation to do so. The very person running that course told his gallery about my work and that is the place where I am now going to have a solo show in the summer of 2015. So in fact the reason why I am having a solo show this summer is because I thought I needed to have some down time and I needed to do some pottery. I made get some good bowls to eat my cereal out of, but it wasn’t that the universe needed me to become a potter; it just needed for me to make a connection between my pottery teacher and the gallery.

Follow whatever stupid silly thing comes out of your heart. If it says go and line up peanuts on a shelf on the third floor, then that might be what you are supposed to do. I would recommend that if someone has a calling whether it is artistic or something else, just follow any hunch that is there and give, there. Give the time to it. It is a funny thing that sometimes it is enough just to say out loud what it is that you want.

- « Previous person: Aviram Rozin

- » Next person: Howard Sheets