You can’t imagine what it was like to turn on the TV and watch Oprah hold up a Kindle with our screen in it and endorse what we had worked on …. or walk down an airplane aisle and see our product being used. I knew that at one time this technology was only an idea. After almost failing more than once, we reached success.

1. What led you to the mission of being a research scientist?

As far back as I can remember I’ve always had an inquisitive sense of wanting to know how things work. This was partially prompted by the era — that of Sputnik, the first space shot by the Soviets. This was the space race to be first on the moon.

I find incredibly invigorating to know the unknown and discover  things that people have never known before. I had this passion in grammar school, high school, graduate school, and throughout my profession. I knew very early this was what my passion was and what I wanted to do.

things that people have never known before. I had this passion in grammar school, high school, graduate school, and throughout my profession. I knew very early this was what my passion was and what I wanted to do.

Even in high school I was fortunate that the high school I went to in Georgia, offered two years of physics and chemistry and quite a bit of math. I took advantage of all those courses early on. I went to a small college named Principia. Principia was not an engineering school. Going to a small undergraduate liberal arts school gave me the extra tools to be able to communicate better. I took courses in philosophy and religion and courses about the world that I would not have been able to take in an engineering school. But I was still a chemistry major. I knew I wanted to go on to graduate school.

I got my PhD from MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)  in chemistry. Graduate school was really about learning how to think. Yes, you have a specific research project, but it is really teaching you how to solve problems and how to do things that are not just recipes in textbooks. You learn how to invent new procedures and new molecules, and new processes.

in chemistry. Graduate school was really about learning how to think. Yes, you have a specific research project, but it is really teaching you how to solve problems and how to do things that are not just recipes in textbooks. You learn how to invent new procedures and new molecules, and new processes.

Learning didn’t stop there. Learning is a lifelong thing. In every stage I wanted to learn more. As my career changed, I went back to school and took solid-state and semi conductor physics and that allowed me to work at the interface between chemistry and electronics. That was even after I had been working for quite a few years. Then later on, both the small college background and additional courses at the Wharton school at the University of Pennsylvania helped me with marketing, sales, and business development.

2. What does this mission mean to you?

I’ve been very fortunate to experience many different aspects of being in research. In the beginning, I was a part of a team and used my knowledge and “cleverness” to solve problems in an industrial environment. We worked as a group because problems today are so  complex that it is very difficult for one person to independently push back the boundaries of science.

complex that it is very difficult for one person to independently push back the boundaries of science.

Then later on I was fortunate enough to be able to lead groups and direct the work of others. Today I lead a very large team of scientists who are actually doing the work. It’s my job to insure that the types of problems that we work on are the most important ones and to make sure that those scientists have the resources and training and the encouragement they need to make progress as a part of that team.

3. What was your best day as a research scientist?

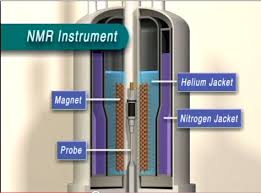

As an individual scientist, I think back in graduate school where I could spend days or weeks of work trying to make a new molecule as a chemist. I finally got some crystals to form in the bottom of a flask. This is after many stages of synthesis. I separated those out and dissolved them and looked at them with an instrument such as NMR.  (This is the instrument used to identify the molecule.) All of a sudden I realized that for the first time in mankind’s history, I had made a molecule that no one else had ever made. It is so exciting to know that you have done something new — of course, with a purpose. These molecules are not just made randomly. They are made with a purpose in mind. That is incredibly exciting. This is about being an individual scientist. (To read an article about chiral lanthanide shift reagents written by Michael McCreary, et.al., click on this link.)

(This is the instrument used to identify the molecule.) All of a sudden I realized that for the first time in mankind’s history, I had made a molecule that no one else had ever made. It is so exciting to know that you have done something new — of course, with a purpose. These molecules are not just made randomly. They are made with a purpose in mind. That is incredibly exciting. This is about being an individual scientist. (To read an article about chiral lanthanide shift reagents written by Michael McCreary, et.al., click on this link.)

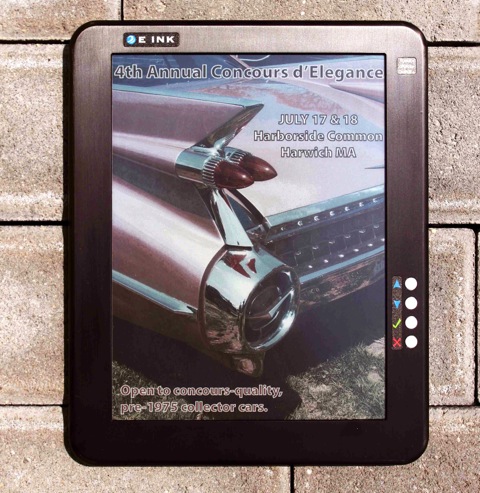

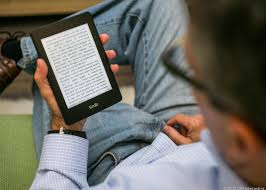

As a leader in science, it is very exciting to be working as a scientist with a team. For instance, at E Ink, it’s been about ten years and  close to one hundred and forty million dollars trying to develop a new type of electronic paper – one that can be read outside in bright sunlight – like ink on paper and not like the LCD in televisions. The purpose was to change the way the world reads. The idea is that rather than having heavy book in your hands, you can have an entire library in your pocket. A whole library can be lighter than a book and very easily you can have access to not just hundreds of thousands of books, but millions of books in seconds – wherever you are!

close to one hundred and forty million dollars trying to develop a new type of electronic paper – one that can be read outside in bright sunlight – like ink on paper and not like the LCD in televisions. The purpose was to change the way the world reads. The idea is that rather than having heavy book in your hands, you can have an entire library in your pocket. A whole library can be lighter than a book and very easily you can have access to not just hundreds of thousands of books, but millions of books in seconds – wherever you are!

After working so hard with a start up company and almost failing more than once in terms of running out of money, we reached success and accomplished our goal. You can’t imagine what it was like to turn on the TV and watch Oprah hold up a Kindle with our screen in it and endorse what I had worked on, and have the sales go to shipping millions a month and being able to walk down an airplane aisle and see our product being used – when I knew that at one time this technology was only an idea to start with. That is incredibly thrilling. The first best day has to do with the scientist working in the laboratory and seeing the results of something no one has ever done before. The second one has to do with being a part of a team where scientists are working together on a very complex problem. So, seeing the world change forever is my best day. One of those changes is seeing there are more people reading electronic books today than paper books. Knowing that change is the result of something I was most fortunate enough to be working with is incredible and thrilling.

screen in it and endorse what I had worked on, and have the sales go to shipping millions a month and being able to walk down an airplane aisle and see our product being used – when I knew that at one time this technology was only an idea to start with. That is incredibly thrilling. The first best day has to do with the scientist working in the laboratory and seeing the results of something no one has ever done before. The second one has to do with being a part of a team where scientists are working together on a very complex problem. So, seeing the world change forever is my best day. One of those changes is seeing there are more people reading electronic books today than paper books. Knowing that change is the result of something I was most fortunate enough to be working with is incredible and thrilling.

4. What was your worst day as a research scientist?

When I went to MIT my first year, I was coming from a small college. I got many wonderful things from that small college. Other people who were coming to MIT were from Brown and other major universities. They were coming with very, very strong undergraduate science backgrounds. I was used to getting all A’s in the sciences courses. In the first year of graduate school there were courses where nobody knew the answers and we had to figure them out – I did very well. But there  was one course on organic synthesis and I really struggled. I didn’t even have a strong enough background to understand the things that were being taught. I fell further and further behind. At the end of the class, it was clear that I was going to fail the class. I don’t remember if I got an F or a D. It was a really bad grade.I went to my graduate advisor and was really down and out. I told him I wanted to drop the course about halfway through. It was clear I wasn’t going to make it. He basically said it would be good for my soul and I needed to finish it. I worked as hard as I could and finished and indeed failed the course. At that point, I was as low as I could get.

was one course on organic synthesis and I really struggled. I didn’t even have a strong enough background to understand the things that were being taught. I fell further and further behind. At the end of the class, it was clear that I was going to fail the class. I don’t remember if I got an F or a D. It was a really bad grade.I went to my graduate advisor and was really down and out. I told him I wanted to drop the course about halfway through. It was clear I wasn’t going to make it. He basically said it would be good for my soul and I needed to finish it. I worked as hard as I could and finished and indeed failed the course. At that point, I was as low as I could get.

Here I was in graduate school. I had gotten into MIT. I was taking a required course and failed it! At MIT, if you don’t make it your first year, you are pretty much let go. They give you a Maters Degree, let  you go, and you are pretty much washed out. So that was definitely my worst day. I had a meeting with my advisory group and they basically said, “What do you want to do? “ I asked them, “What do I do?” They told me I should take an undergraduate course in organic chemistry. Then they would make a decision what to do from there. I had to go back as an undergraduate student and take a course that had two or three hundred people in it in a huge amphitheater. There were all the brilliant MIT undergraduate students. I took this course while I was doing this research and taking my other courses. I received a final grade of A in the class.

you go, and you are pretty much washed out. So that was definitely my worst day. I had a meeting with my advisory group and they basically said, “What do you want to do? “ I asked them, “What do I do?” They told me I should take an undergraduate course in organic chemistry. Then they would make a decision what to do from there. I had to go back as an undergraduate student and take a course that had two or three hundred people in it in a huge amphitheater. There were all the brilliant MIT undergraduate students. I took this course while I was doing this research and taking my other courses. I received a final grade of A in the class.

5. How did you survive your worst day?

By not quitting and not getting discouraged, it turned out really, really well. It turned out that I passed first or second in that class with several hundred people. At that point, my advisory group  was solidly behind me. I finished my other research. What helped me was talking to my advisor, George Whitesides. I was trying to decide what I should do because this had been my lifelong passion to be a research scientist. He was this prominent research scientist who had taken me on in his research group. When we tried to talk during the day, he would be busy with all this other responsibilities.

was solidly behind me. I finished my other research. What helped me was talking to my advisor, George Whitesides. I was trying to decide what I should do because this had been my lifelong passion to be a research scientist. He was this prominent research scientist who had taken me on in his research group. When we tried to talk during the day, he would be busy with all this other responsibilities.

I tended to work pretty late until one or two in the morning. He came by early morning and I was in tears. I told him about the class I was failing. He asked me what I wanted to do. I said I didn’t know what else I would do. It was the only thing I had ever wanted to do my whole life – to be a research scientist. I asked him, “What  would you have done if it hadn’t worked out for you?” He only paused a second and he said, “You know, I think I would have been a farmer or gone into farming.” That answer was perfect because here was a potential Nobel Prize winner and what I got out of that answer was: you can pick anything and if you are striving for excellence and fulfillment, it doesn’t matter if you are a research scientist or farmer. What is important is that you are doing the best you can at what you do. What is important is doing something that is helping others – as farming is – and doing something that you enjoy doing. His answer made me realize everyone has an important place in the world. This was the perfect answer he could have given me at this period of time and it freed me up for the rest of my life. I’m basically a positive person at heart.

would you have done if it hadn’t worked out for you?” He only paused a second and he said, “You know, I think I would have been a farmer or gone into farming.” That answer was perfect because here was a potential Nobel Prize winner and what I got out of that answer was: you can pick anything and if you are striving for excellence and fulfillment, it doesn’t matter if you are a research scientist or farmer. What is important is that you are doing the best you can at what you do. What is important is doing something that is helping others – as farming is – and doing something that you enjoy doing. His answer made me realize everyone has an important place in the world. This was the perfect answer he could have given me at this period of time and it freed me up for the rest of my life. I’m basically a positive person at heart.

When I am having a bad day, I pretty much take a deep breath and pause and keep going through it. I go home and take another deep breath and get a good night’s sleep. When I do get up the next day, it is a new day and it’s not the bad day any more and that day is a good day and I know that it will be a good day. I think that is the main thing – believing and knowing and making the good days after the bad days – knowing that the next day can be a good day. To some degree it is what you make of it, but I know it isn’t always as simple as that. You just have to remember that there can be good days after the bad days.

The fear that all the other days are going to be bad days after the good days is what can make a bad day oppressive. If you believe that there will be a lot of good days after the bad days, the bad day isn’t so bad. I feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity during my life to do what I’m passionate about and have opportunities to change the world. I hope that everyone has the opportunity to find things that really make them excited to go to work every day. I hope they find opportunity and fulfillment in their mission and more than just a job to make money or to pay the bills. I pray and hope everyone has that opportunity as I have.

- « Previous person: Lois Severin

- » Next person: Deborah Pierce