One kid in his late teens or early twenties came up to me and said, “You know listening to your show changed my entire life.” One of those things that I am very well aware of is the transformative power of music to make people feel better and make people think about things.

1. What led you to the mission of being the host and producer of Jazz Unlimited St. Louis Public Radio KWMU 90.7?

When I was in high school in 1959, I saw a very famous jazz group called the Miles Davis Sextet.  In addition to Miles Davis on trumpet, there was John Coltrane on tenor sax and Cannonball Adderley on alto sax. At that point I decided that that was the only kind of music I wanted to hear.

In addition to Miles Davis on trumpet, there was John Coltrane on tenor sax and Cannonball Adderley on alto sax. At that point I decided that that was the only kind of music I wanted to hear.

Even in high school I was a research type person. I started studying the history of jazz. I started collecting recordings. Throughout college I went to the University of California, Riverside and earned a bachelor’s and a PhD in chemistry. I still kept collecting jazz recordings.

(Dennis’ radio program Jazz Unlimited is broadcast on Sundays at 9:00 pm until midnight Central Standard Time USA. You can listen to Jazz Unlimited on the radio or on the free St. Louis Public Radio App for phones, computers or tablets. Listen on the app anywhere in the world that has cellular or Wi-Fi service. Past programs are in the archives.)

(Dennis’ radio program Jazz Unlimited is broadcast on Sundays at 9:00 pm until midnight Central Standard Time USA. You can listen to Jazz Unlimited on the radio or on the free St. Louis Public Radio App for phones, computers or tablets. Listen on the app anywhere in the world that has cellular or Wi-Fi service. Past programs are in the archives.)

I married my first wife Rosa in 1963. We moved to St. Louis in 1969 and I took a job with Monsanto. When I finished there in 1966, I was a Senior Science Fellow. Monsanto was roughly a six billion dollar corporation.

Lindenwood College radio (KCLC) had a jazz program in the 70’s. A guy by the name of Kaylock Sellers ran it. I got to know him by calling in about a few things he was playing and asking questions. I kept collecting and studying. (Below is a video about Dennis’ jazz photography collection.)

After Cannonball Adderley died, Kaylock called me and said, “Would you like to do an hour and a half or so program in tribute to Cannonball Adderley?” I said, “Well, I’ve never done this before but what the heck, I’ll do it.” That is one of the things about me is that I’m never afraid to take a leap and do something I have never done before. So I did the program.

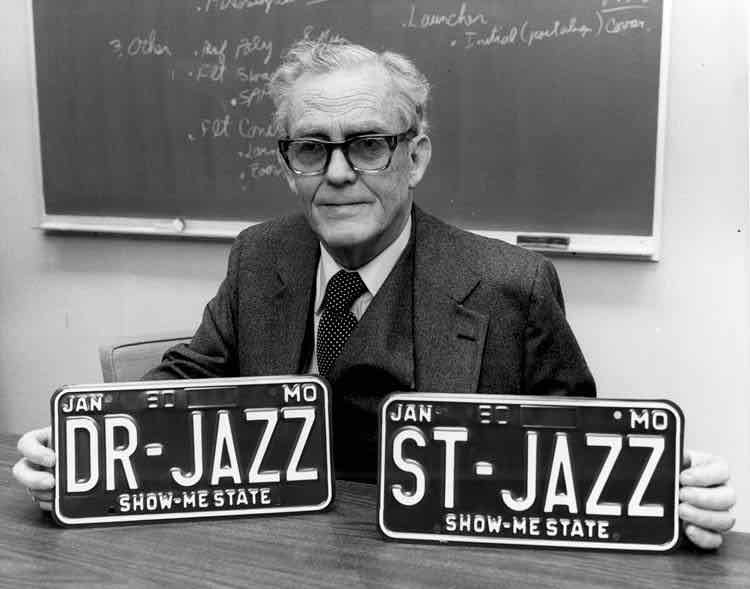

I listened to Leo Chears in East St. Louis. I was also listening to Charlie Menees on KWMU and I got to know him through classes he was giving on jazz history. Leo cheers is pictured to the right in a red vest and Charlie Menees with the license plates.)

I listened to Leo Chears in East St. Louis. I was also listening to Charlie Menees on KWMU and I got to know him through classes he was giving on jazz history. Leo cheers is pictured to the right in a red vest and Charlie Menees with the license plates.)

Then Charlie left KWMU to go to KMOX. To make a long story short, I started doing some guest hosting with Romondo Davis who was Charlie’s engineer and who replaced him.  Romondo left and Jim Wallace took over the program. Jim kept calling me up to do shows. We talked. One day we decided to continue as co-hosts of the show. I started doing that show in 1983 and did it until 1986. Then I got my own show and moved from Saturday to Sunday night. (Click here to visit Dennis Owsley’s website.)

Romondo left and Jim Wallace took over the program. Jim kept calling me up to do shows. We talked. One day we decided to continue as co-hosts of the show. I started doing that show in 1983 and did it until 1986. Then I got my own show and moved from Saturday to Sunday night. (Click here to visit Dennis Owsley’s website.)

In the mean time, I had gotten a grant from the Regional Arts Commission to do a radio history of jazz in St. Louis. I did the show and it ran for nineteen hours on the air. As far as I know it was the second longest music documentary in the history of radio.

I continued to do a show on Sunday nights. I followed Walter Parker who played the older music. He was in his 80’s. When he retired, I got an extra hour so I added in the older stuff too.

I’ve been doing the Sunday night Jazz Unlimited show ever since.  In 2003 the Sheldon Concert Hall contacted me about writing a book. I had all of these interviews from the 1980’s documentary. That led to the basis of the book and an exhibition that I co-curated with Olivia Lahs-Gonzales at the Sheldon in 2006. There was also a concert at the Sheldon that I produced that had to do with the book and the exhibit. The concert got three standing ovations. The book is named City of Gabriels: The History of Jazz in St. Louis 1895-1973. (Click here to buy a copy of the book.)

In 2003 the Sheldon Concert Hall contacted me about writing a book. I had all of these interviews from the 1980’s documentary. That led to the basis of the book and an exhibition that I co-curated with Olivia Lahs-Gonzales at the Sheldon in 2006. There was also a concert at the Sheldon that I produced that had to do with the book and the exhibit. The concert got three standing ovations. The book is named City of Gabriels: The History of Jazz in St. Louis 1895-1973. (Click here to buy a copy of the book.)

Over the years I have also given lectures and adult education classes about jazz. To celebrate my thirtieth year on the air, I put together a new radio documentary on the jazz history of St. Louis. That documentary ran for thirty hours which is now the second longest music documentary in radio history. The 1981 documentary became the third longest. I’ve continued on in radio and on April 23rd, 2015 I will have finished my thirty-second year and begin my thirty-third year in broadcasting mostly at KWMU in St. Louis.

2. What does this mission mean to you?

I found that jazz music always makes me feel better. One of those things that I am very well aware of is the transformative power of music to make people feel better and make people think about things.  One thing about jazz musicians that people are unaware of is that the jazz family is probably the only true meritocracy in existence. To the musicians, the only thing that matters is how well you play, not what color you are or how rich you are. The musicians don’t discriminate about these things, but unfortunately audiences and people in the music business do. Because of this meritocracy, I never announce the race of the musicians on my show.

One thing about jazz musicians that people are unaware of is that the jazz family is probably the only true meritocracy in existence. To the musicians, the only thing that matters is how well you play, not what color you are or how rich you are. The musicians don’t discriminate about these things, but unfortunately audiences and people in the music business do. Because of this meritocracy, I never announce the race of the musicians on my show.

I structure my shows so that I’m teaching about what jazz is and its history. I hope that the way some of the titles are put together, the listener will think about what I am saying with the titles. For instance, I did a program last week on Duke Ellington. I played a suite of his called The Deep South Suite. The first part has to do with the Dixie Chamber of Commerce in the south in 1940. The second part had to do with stuff they didn’t talk about – like lynching. The third part is about a little train that goes through the south and the black fireman is tooting the whistle and greeting everybody. The fourth part has to do with races getting together on the sly.

I also did music from a review of his called Jump For Joy, a show that celebrated the Emancipation Proclamation.

I do an annual winter holiday show that plays music suggestive of all the various religious and cultural celebrations that take place during the time of the winter solstice. Last year for three hours, every song had the word “peace” in it. So there is a little bit more than just playing the music. I’ve had people tell me how good it makes them feel when they hear the show. One young man in his late teens or early twenties came up to me and said, “You know listening to your show changed my entire life.” I feel like I am doing something good for the community.

One of the things that the show helped me with was when my wife died suddenly in 2008. I was able to work out some of my grief and fears on the air through music. The show helped me get through that year.

One of the things that the show helped me with was when my wife died suddenly in 2008. I was able to work out some of my grief and fears on the air through music. The show helped me get through that year.

I record the show on my computer. I’ve been doing it this way since 2006. I used to go in to the station, take the recorded show and do the local breaks — like the weather, live. But, I wasn’t coming out of the station until after midnight. There was nobody around at that time in the morning.

Now we have automation at St. Louis Public Radio. I take the program in on a flash drive. I load it into the automation. The station has someone who records the local breaks. The show is assembled through automation and nobody has to be there at night. If I’m out of town and don’t have the time to record shows ahead, I can pull up one of over four hundred and fifty shows that I’ve done and are stored digitally on my computer.

3. What was your best day being host and producer of Jazz Unlimited St. Louis Public Radio KWMU 90.7?

One best day was just recently when I completed that thirty hour documentary. I put in at least four hundred and fifty hours on that thing to get it all together. Another was a celebration of my 25th year at Jazz at the Bistro with a proclamation of a “Dennis Owsley Day” in St. Louis by the mayor.

4. What was your worst day being on the air?

I found a recording by a man by the name of Sun Ra in Houston at the end of a chemical plant start-up. He was an avant-garde pianist who claimed he was from Saturn. The album was an extended play piece called Nuclear War.  I always played that kind of wild stuff at the end of my program around 11:00 pm to midnight. At the last minute, I decided to play Sun Ra’s recording. A minute into the piece, Sun Ra’s voice came on and chanted, “Nuclear war. It’s a M…F…” (Words not appropriate for public radio.) There were also phrases like, “When the bomb falls, we’re all going to go, so kiss your a… goodbye, goodbye.” There was stuff like that throughout.

I always played that kind of wild stuff at the end of my program around 11:00 pm to midnight. At the last minute, I decided to play Sun Ra’s recording. A minute into the piece, Sun Ra’s voice came on and chanted, “Nuclear war. It’s a M…F…” (Words not appropriate for public radio.) There were also phrases like, “When the bomb falls, we’re all going to go, so kiss your a… goodbye, goodbye.” There was stuff like that throughout.

When Sun Ra’s piece played, the guy who was engineering at the time had temporarily stepped out of the booth. So these words got repeated about three times before I could run over there and shut it off. The broadcast was live. I thought, “Oh my God. I’m going to jail.”  In the artistic context of the piece, Sun Ra could get away with that language. The rules were very loose on what could be said on late night radio in the mid 1980’s. Very, very loose. But this was not the case at the time we were playing the piece. People were calling in and saying, “Why did you shut it off?” The last person who called in was a minister who was listening. He was going to call the general manager and the FCC. He did call him and I was asked to give the manager a copy of the piece. The manager made a comment to me but nothing more was said. I learned at that point to never play something that I hadn’t listened to. That is my worst story.

In the artistic context of the piece, Sun Ra could get away with that language. The rules were very loose on what could be said on late night radio in the mid 1980’s. Very, very loose. But this was not the case at the time we were playing the piece. People were calling in and saying, “Why did you shut it off?” The last person who called in was a minister who was listening. He was going to call the general manager and the FCC. He did call him and I was asked to give the manager a copy of the piece. The manager made a comment to me but nothing more was said. I learned at that point to never play something that I hadn’t listened to. That is my worst story.

5. How did you survive your worst day?

I was scared to death. I told the general manager, “Well, I’ll not do the show any more.”  He said, “No. That’s fine. Just make sure next time.” I didn’t sleep for about two days. I thought, “Oh my God. What did I do? The FCC is going to come after me.” But nothing happened.

He said, “No. That’s fine. Just make sure next time.” I didn’t sleep for about two days. I thought, “Oh my God. What did I do? The FCC is going to come after me.” But nothing happened.

My wife Rosa helped me. She sympathized. The funny thing was that the next day she took our son to the pediatrician’s office. It turns out he was a fan of the show. He said, “I heard something on the radio last night that I never thought I would hear in my life.”

When you do something dumb like that, you just move on. You apologize. You move on and you never do it again.

6. What advice do you have for someone who would like to be a host and/or producer of a radio show?

It’s something that you do because you love to do it – even if you can’t make money or it is just a hobby. A lot of people get started in college radio and may not be getting a communications major. The way you get into public radio is to volunteer at a public station and eventually if you are good enough to do that kind of work, then you do it. I don’t think that people who have broadcast degrees do any better than people who just have a gift of gab and walk in and do it. Volunteer. Do it because you love it.

- « Previous person: Julie Harwell

- » Next person: Doug Smith