Person of the Week

Andrea Adams

Archeologist, Anthropologist, Archivist, Project Manager Veterans Curation Program

Mindsets about archeology have changed a lot. It used to be like a treasure hunt. For me the treasure is doing my part to educate people about their history. It’s cool!

1. What led you to the mission of being an archeologist, anthropologist, archivist and Project Manager for the Veterans Curation Program?

I grew up in a very rural town. My family had farmland. My dad and I would walk on the land and try to find artifacts. I would collect shiny pieces of pottery or glass – or anything! I loved doing that but I always wanted to take it a step further. I would collect stuff in the field after it had been plowed up and then I would wash everything  and sort it by colors. Even as a child I loved organizing and categorizing things.

and sort it by colors. Even as a child I loved organizing and categorizing things.

My mom was a teacher and I always loved teaching and education. I played around with this idea of wanting to be a teacher and wanting to do something that I loved – which was archeology.

When I went to the University of Georgia, I thought about teaching. I didn’t know any archeologists. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. My parents were incredibly supportive of anything I did. They told me, “Take a chance. Why not do what you love!” But some people had discouraged me – as they do with most archeologists. Their questions were, “But where are you going to get a job? You’re never going to get paid to do this!” But I decided to just take a chance on it.

I was in an archeology class at the University of Georgia and did extremely well because I loved it. The professor realized it. He asked me to start working at the Georgia Archeological Laboratory at the University of Georgia. I worked with the documents that they used to record archeological sites all over the state of Georgia. There are thousands and thousands of sites. What we need is for people to record those so that if someone wants to build something on that site, they will know that there is an archeological site in that area.

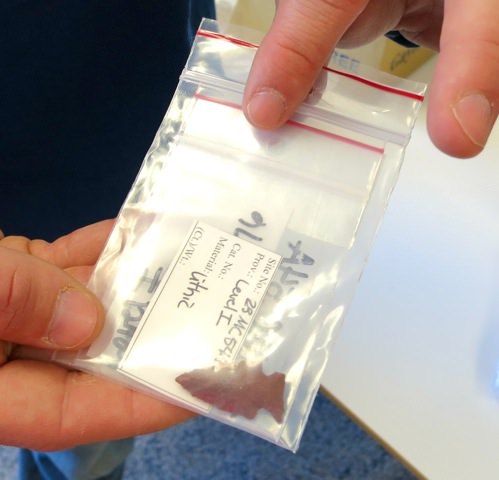

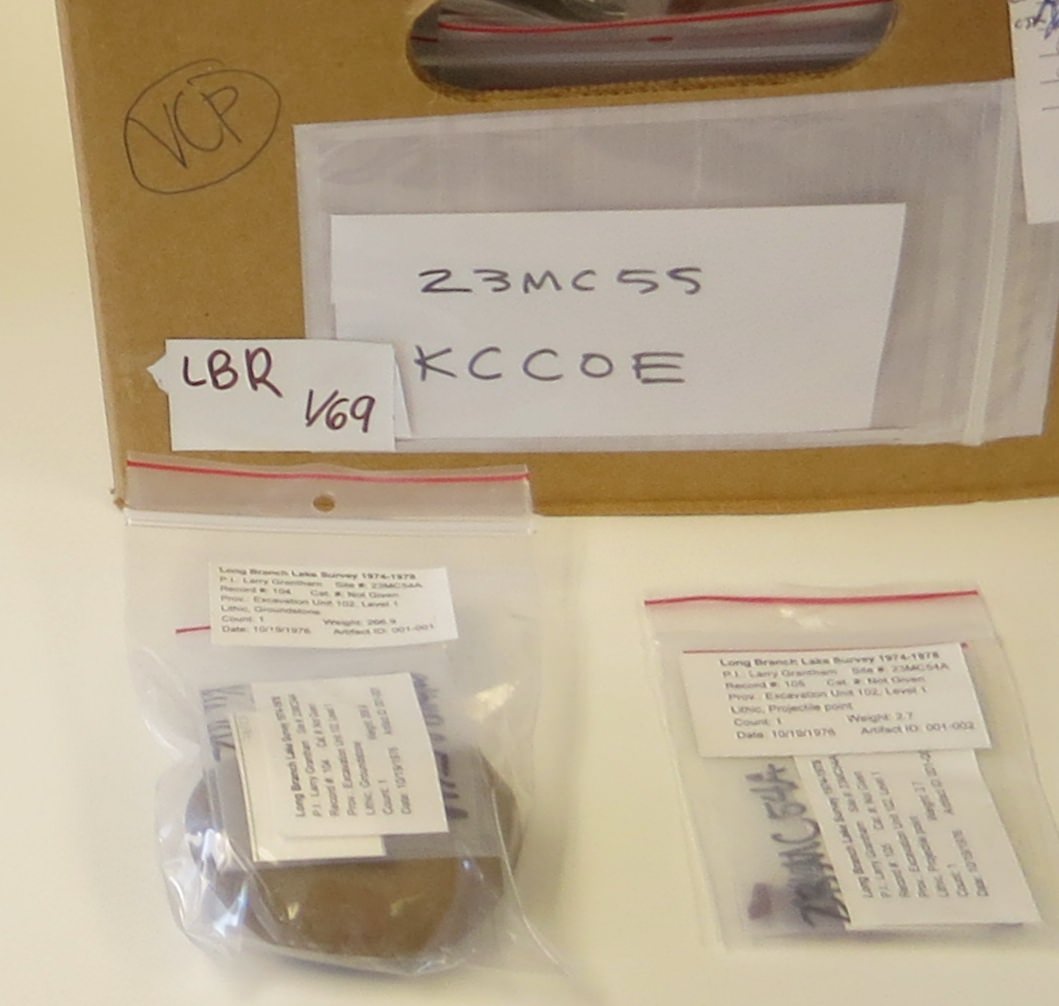

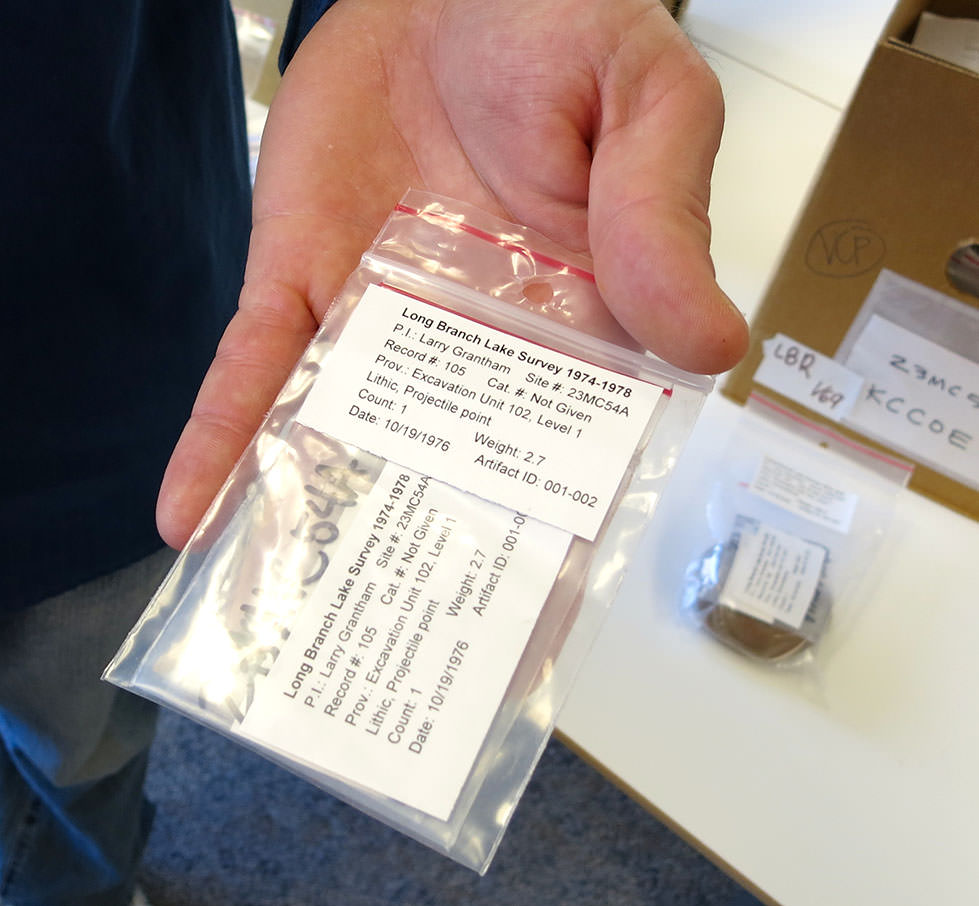

I worked with the document side of things and archeological reports. Artifacts are cool but they are also important and you need the  associated documents to tell you what you are looking at and where it was found. That is how the artifacts gain their meaning. The context in which they were found is important. Instead of just having a piece of pottery, you can tell a story. For instance, you can say, “That piece of pottery was found at a village and they were cooking with it or they were using it for ceremonial purposes.” You need all those pieces coming together to really grasp history and pre-history.

associated documents to tell you what you are looking at and where it was found. That is how the artifacts gain their meaning. The context in which they were found is important. Instead of just having a piece of pottery, you can tell a story. For instance, you can say, “That piece of pottery was found at a village and they were cooking with it or they were using it for ceremonial purposes.” You need all those pieces coming together to really grasp history and pre-history.

That was my first job as an archeologist. It was all because of this professor who believed in me and gave me a chance. This made it possible for me to get into archeology.

I did the art history degree because I love art. There is a link between archeology and art history. You look at the beautiful pieces of pottery and you see all kinds of people trying to express themselves through materials. That fascinated me, so after getting my degree, I took a year off to do work at different places like house museums and excavating at archeological sites. I knew that it was something that I wanted to do and I could do.

I decided to get my master’s degree at the University of Alabama. This took two years. I was waiting around to graduate. I had already written my thesis. I had already done my coursework. But as you know, you are kind of in purgatory for a while until you actually get your degree. So I started applying for jobs pending my master’s  degree.

degree.

I had a couple of job offers from different places. Nothing seemed right. I thought, “Well, I can hang on a little bit longer.” I got a call one day from a contracting firm. I didn’t start out with the Corps of Engineers. I started out as a contractor working in a lab. This woman called and told me about a job. She asked if I wanted it. I have no idea why, but I said, “Yes.” I didn’t even know that much about it at the time. I talked to her again and asked, “I’m sorry, but what exactly is the gist of this job? What will I be doing in this program?” I knew that I would be working with veterans. I would be using archeology to help them. “All right. I’m on board for that!” Two weeks later, she told me, “You’re starting in two weeks. We need you a week from now to do an introduction. Then we need you to move.”

My parents helped me load up two cars and my family drove me to a new city. They spent the whole Thanksgiving weekend settling me into a new apartment that I had rented sight unseen. Taking this job just seemed like the right thing to do. I took a leap of faith. I thought it would only be for a year. I knew that if I didn’t like it, I could move on and do something else. I ended up absolutely falling in love with the job at the Veterans Curation Program. I was a contractor for one year working in the lab. I was the Archives Supervisor. What I did was help to train the veterans on preserving the records associated with archeological investigations.

After a year the director, Dr. Michael “Sonny” Trimble [AEA1] recognized that I and another person Kate McMahon were a benefit to the program. We were doing a good job with this program and keeping it afloat. We were able to get congressional funding. The money was only supposed to last one year. But because the program ended up being a success, we continued to get funding. This money goes into hiring more veterans. At that time, Kate and I were able to transfer over from being contractors to being able to work for the Corps of Engineers.

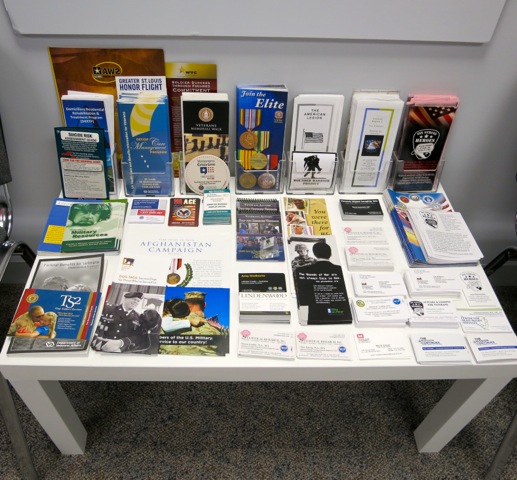

Now our job is not just working in one lab, but we supervise all three labs. They are in St. Louis, Missouri, Alexandria, Virginia serving the  metro Washington D.C. area, and in Augusta, Georgia. We are the project managers. We focus on the artifacts and archives side of things. Our goal is to help preserve these archeological collections and also help veterans who are wounded and disabled and recently separated from the service. The first year out of the military can be very difficult time. Many veterans face unemployment, and even suicidal thoughts. Coming back from the military, veterans may not know what they are going to do with their life. (Pictured are other services and opportunities offered to participating veterans. Resume building, job fairs, and practice in interviewing are a part of the program.)

metro Washington D.C. area, and in Augusta, Georgia. We are the project managers. We focus on the artifacts and archives side of things. Our goal is to help preserve these archeological collections and also help veterans who are wounded and disabled and recently separated from the service. The first year out of the military can be very difficult time. Many veterans face unemployment, and even suicidal thoughts. Coming back from the military, veterans may not know what they are going to do with their life. (Pictured are other services and opportunities offered to participating veterans. Resume building, job fairs, and practice in interviewing are a part of the program.)

Sometimes we pound the pavement and work with Veteran Affairs to find veterans for the program. We get veterans out of their comfort zone. Some of the vets might have an interest in archeology and may have watched a couple of shows on the history channel, but they don’t really know what it is. It is a leap of faith to even come and work with us.

The program is about making veterans feel comfortable and showing them they don’t need to know anything about archeology to start the program. We teach them everything they need to know. We tell them, “You are going to do a good job at it.” This really is a wonderful program.

This job combines my two loves — doing archeology and helping by teaching. The first month it is really like archeology 101. We teach them how to process the artifacts and documents. After that we get them to start processing the collections. They work like they would in any normal job – doing the work. But we also do professional growth and development and get out of our comfort zone. We help them do resume building, mock interviews, online job searches, and we take them to career and job fairs. We also have events and Meet and Greets to get them connected to people in the community who can employ them after their work here.

For the veterans, trying to get a job after the program is hard and daunting. They might be worried that they are not qualified.  Rejection letters can be a hit to them personally. We build up their confidence level and help them search for jobs that fit their interests and expertise. We help them see the good about themselves. Sometimes they don’t even see their own good and the all the awards and honors they earned in the military. They may have been deployed three times or have a Purple Heart. We tell them to put this on their resume. A lot of times they will tell us that their military experience doesn’t translate to civilian jobs. We tell them military work does matter. We tell them how they supervised people or they tracked equipment – equipment that costs millions of dollars. That is a lot of responsibility. Of course that is job experience. Helping other people realize their passion is hard to do, but it is one of the best things we do. We have an eighty-six percent rate for getting veterans employed or getting them into educational opportunities after the program. (Pictured is Doug Blain, veteran and experienced participant rehabilitating and rehousing collections and using the most current and effective techniques known to curation and archival specialists.)

Rejection letters can be a hit to them personally. We build up their confidence level and help them search for jobs that fit their interests and expertise. We help them see the good about themselves. Sometimes they don’t even see their own good and the all the awards and honors they earned in the military. They may have been deployed three times or have a Purple Heart. We tell them to put this on their resume. A lot of times they will tell us that their military experience doesn’t translate to civilian jobs. We tell them military work does matter. We tell them how they supervised people or they tracked equipment – equipment that costs millions of dollars. That is a lot of responsibility. Of course that is job experience. Helping other people realize their passion is hard to do, but it is one of the best things we do. We have an eighty-six percent rate for getting veterans employed or getting them into educational opportunities after the program. (Pictured is Doug Blain, veteran and experienced participant rehabilitating and rehousing collections and using the most current and effective techniques known to curation and archival specialists.)

2. What does this mission mean to you?

Mindsets about archeology have changed a lot. It used to be like a treasure hunt. But for me the treasure is doing my part to educate people about their history. It’s cool! I’ve always been interested in history and I’ve always liked the idea of preserving things. A lot of times people throw their history away. It’s hard for me to see that.

It is wonderful to be at a site that hasn’t been seen in two thousand  or four thousand years. I really love that. I love opening boxes that have been sitting on the shelves for the past sixty or seventy years. I might say, “Wow. Look at that. I’m bringing this to the light of day.”

or four thousand years. I really love that. I love opening boxes that have been sitting on the shelves for the past sixty or seventy years. I might say, “Wow. Look at that. I’m bringing this to the light of day.”

We had some photographs from the 1880’s where they were using a mule team to build a levee on the Black Warrior River in Alabama. They were incredible. What we were able to do to preserve those photographs was to create a digital copy. The Corps’ Mobile District was able to put those on display. All of the materials that we are digitizing, the documents we are scanning, and the artifacts that we are taking pictures of, eventually will go online. We are going to have a digital collection that people are going to be able to search through. We will put it on the Digital Archaeological Record (tDAR) at Arizona State University and teachers will be able to use this as material for curriculum. (Check out Digital Archaeological Record site by clicking here.) They’ll be able to teach classes from these materials. For instance, they will be able to use archeology to teach the metric system or how to use a compass.

3. What was your best day as an archeologist, anthropologist, archivist and Project Manager for the Veterans Curation Program?

There have been a lot. We had a Meet and Greet for the Veterans Curation Program. We had this incredible turn out and five or six of the former technicians showed up. I knew them because I was supervising when they were going through the program. That was amazing. I got to see what they were doing at that point. One person  told us, “You helped change my life.” That was a big deal to me. I didn’t take that lightly. It was wonderful seeing them.

told us, “You helped change my life.” That was a big deal to me. I didn’t take that lightly. It was wonderful seeing them.

While in the program, one of the guys mentioned he liked doing EMT (Emergency Medical Technician) and volunteer work. We knew that he had gotten into a training program. We didn’t know if he had finished it. But, sure enough, he came back and he was in his EMT uniform. He had gotten his training and certification to be an EMT and was on his lunch break.

Just knowing that I’m doing a very small part to help somebody – that’s really nice to know. It is those meetings like the Meet and Greet that we get to show off the program and talk about how wonderful it is. It meant a lot that day to see program praises coming from the veterans. It’s been nice being involved with a program that is successful. It was a nice event because I got to see some of the people that I wouldn’t have gotten to see. Everyone was doing well.

My favorite archeology moment was when I working for the Office of Archaeological Research at Moundville, Alabama. They were doing a museum renovation project in the summer. It was around 100 degrees every single day. We had this little shade tent. I was writing my master’s thesis at night and working full time during the day. Looking back, I don’t know how I was able to do all that.

We were excavating at this large ceremonial site from about 1000 AD. Evidently they threw this incredible potluck party. They had dug this big hole. When they were through with the party, they  threw all their trash in this big pit. We joke about archeology that we are pretty much just digging through people’s trash and we are so excited about it. That’s what it was – a big trash pit. The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) had built a road over this site. Under the road was this pit that was from about a thousand to fifteen hundred years ago. That was a long time ago. They had put this gravel road down. We had pick axes. It was hot. We were axing though this road. Finally we got to the pit. We found evidence of the food. We had the bones and we could tell what they were eating. We could tell what their pottery looked like. When they were done with the food, some would even throw the vessel in as well. We had all these wonderful artifacts.

threw all their trash in this big pit. We joke about archeology that we are pretty much just digging through people’s trash and we are so excited about it. That’s what it was – a big trash pit. The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) had built a road over this site. Under the road was this pit that was from about a thousand to fifteen hundred years ago. That was a long time ago. They had put this gravel road down. We had pick axes. It was hot. We were axing though this road. Finally we got to the pit. We found evidence of the food. We had the bones and we could tell what they were eating. We could tell what their pottery looked like. When they were done with the food, some would even throw the vessel in as well. We had all these wonderful artifacts.

I travel to different labs. One I’m working on now is at the U.S. Heritage and Education Center. It’s in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. It’s where the Army generals’ and soldiers’ documents go usually after they are dead. There are all these amazing collections. The last collection I went through was Wild Bill Donovan (William J. Donovan) who started at the OSS (Office of Strategic Services). He is known as the Father of the CIA. If you are a general, your private life is public. I got to see the letters he wrote to his son and to his wife. I got to learn about all the amazing trips he went on. I thought, “This is Bill Donovan, an amazing American figure.” We get to go through all this material, do an assessment, and then tell the Heritage Center about the documents, how some might be deteriorating, and then do triage to explain how efforts need to be focused to preserve this information.

I was hoping that my reward for doing this work is to see some enlistment papers signed by Abraham Lincoln. I’ve been told that I get to look at them one day! So I am holding out hope for that moment. If I were to answer this question in a month or two, I might add, “Seeing the enlistment papers signed by Abraham Lincoln.”

4. What was your worst day as an archeologist, anthropologist, archivist and Project Manager for the Veterans Curation Program?

One of the most heartbreaking things that I had to experience in this work was when I was an undergrad. I decided to take on an extra project. I was helping an archeological firm to excavate a family cemetery. This was a little town that had cross streets and a company came in and decided to build a new store on one of the corners. I was so excited to do this project. I agreed to do the project because the corporation had agreed to do the right thing.

The cemetery was associated with a plantation. There was a Civil War soldier buried there. There was a young woman, her parents  who owned the plantation, and her husband who was a Civil War soldier. There were about eight to ten people buried in the family plot.

who owned the plantation, and her husband who was a Civil War soldier. There were about eight to ten people buried in the family plot.

We were excavating for a couple of weeks. This was a gorgeous site. There were these granite slabs to serve as a fence around it. I understand progress. But it was really frustrating to see this plot being developed when there was so much other open land for this rural construction. They could have put it anywhere, but they decided to put it over this cemetery.

One day a bulldozer came in and took all those granite pieces away and put them in a dumpster. I think they could have moved them to another location, but that would have cost more money. That’s when the downhill started.

The excavation was done. We were ready to remove the remains. The corporate people in suits came out there and we told them we were ready to reinter these people. We asked them where they wanted us to do this. Because this was a Civil War soldier, they were going to give us pine boxes to put the remains in and give them a proper ceremony and military burial.

When they came, they said, “Oh don’t worry about it. Just bury them over there.” They gave us plastic moving totes for the remains. We got the dirt, human remains, and casket goods and had to put them in what was given to us. That was heart breaking. This family had owned all of this land. They had farmed it. This was their resting  place. They deserved to be treated with respect.

place. They deserved to be treated with respect.

For that to happen was really hard. I saw what a part of corporate America thought about this. I valued history so much and involved myself in this project because I thought I was doing my part. But for this to happen, it was really hard.

Later on I went around to a couple of little stores and met the locals. One of the women told me that that these people were her ancestors. When I asked why no one had spoken up, the reply was that they were afraid they would be charged money to reinter these people. I explained to them that if they had stepped forward, and told them these were their family members, that would have given us the power to influence the way the individuals were buried. The ancestors would have been able to get a proper burial at no cost to the descendants.

As archeologists, we aren’t treasure hunters. We aren’t digging this stuff up so we can look at it and put it on shelves and keep it from people. We want to involve people in the process and enable everyone to learn from history. One of the difficult things about this and other disheartening stories is that when I first came out of grad school I was so idealistic about everything. I was thinking, “This is going to be amazing!” But at times the hard life lesson is that you can’t help everyone. If I am working with someone who can’t be helped then I have to focus on the people who need my help and will accept my help. I must let people take responsibility for their own situations.

5. How did you survive your worst day?

Chocolate! Another way that I cope is to choose to align myself with companies that have a strong standard and work ethic. That is one of the things I love about the Corps of Engineers. People like Dr. Michael “Sonny” Trimble, my boss, give me the strength and encouragement to do the right thing and voice my opinions. I feel like I am truly being heard. I have decided not to give up. My work is something that I love and there are always going to be opportunities to grow wiser.

[AEA1]This is how we usually type it.

- « Previous person: D.Y. Begay

- » Next person: Ingrid Murphy